Climate change is expected to fundamentally alter the function and character of plant communities, but how the native and exotic components of plant communities will respond to climate change remains an open question in ecology. Invading plant species can achieve greater success in to novel habitats through adaptation, and climate change could change niche relationships within a community to either advantage resident exotic species or create opportunities for further invasion.

My work is motivated by a desire to identify differences in the potential for adaptation between native and exotic plant species, to understand how ecological forces shape the potential for adaptation, and to understand how (and why) climate change might differently impacts native and exotic plant species.

Ecological sources of intraspecific and interspecific variation in adaptability

The likelihood that a population will respond to natural selection will depend on the ability of selection to act on standing genetic variation in the face of genetic drift. Drift can be empirically estimated as the effective population size (Ne), and interspecific variation in Ne has been attributable to differences in census population sizes, generational changes in population sizes, variance in reproductive success, unequal sex ratios, and taxonomic signal. It is also possible that ecosystem or community level properties, such as species diversity, productivity, climate, disturbance and invasion could similarly impact the Ne of constituent species, either directly or through their effect on population level metrics. I am using estimates of Ne from genomic data to better understand adaptability across communities and populations to better understand how differences in adaptability arise across species, how adaptation may vary across invasion, and how adaptation could factor into how plant communities, particularly the native and exotic components of communities, will respond to climate change.

Intraspacific variation of Ne in biological invasion

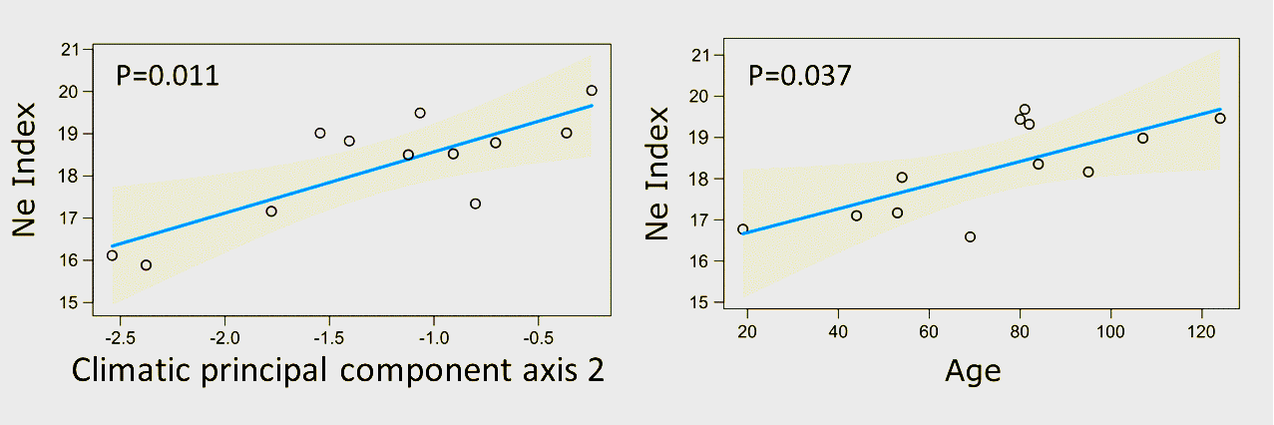

Genetic drift is expected to play a larger role in the evolution of colonizing and invading species because of the potential for demographic bottlenecks and unique sampling effects associated with range expansion. I am currently using genomic data for the Eurasian weed Centaurea solstitialis (Yellow starthistle) to characterize Ne variation in its invaded and native ranges. In the invaded range, younger populations have lower Ne, as predicted by models of range expansion. Populations located in areas that tend to have greater seasonal differences in temperature and precipitation tended to have larger Ne, supporting the assertion that ecological factors may act as drivers of Ne variation.

Interspecifc variation in Ne

If ecology matters for shaping intraspecific differences in Ne, then biological communities may be subject to conditions which will similarly impact Ne across multiple species. For example, fluctuations in population size in response to differences in precipitation occur in annual plant populations. The degree to which ecological variation might influence across co-occurring species Ne is currently unknown. Importantly, the different ways in which individual plant species cope with environmental variation may also reflect the size of Ne.

I am working in three distinct herbaceous plant communities (McLaughlin Reserve, California;; and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, Colorado; Tumamoc Reserve, Arizona) to characterize the distribution of Ne. I am also comparing the distribution of Ne across communities.

If ecology matters for shaping intraspecific differences in Ne, then biological communities may be subject to conditions which will similarly impact Ne across multiple species. For example, fluctuations in population size in response to differences in precipitation occur in annual plant populations. The degree to which ecological variation might influence across co-occurring species Ne is currently unknown. Importantly, the different ways in which individual plant species cope with environmental variation may also reflect the size of Ne.

I am working in three distinct herbaceous plant communities (McLaughlin Reserve, California;; and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, Colorado; Tumamoc Reserve, Arizona) to characterize the distribution of Ne. I am also comparing the distribution of Ne across communities.

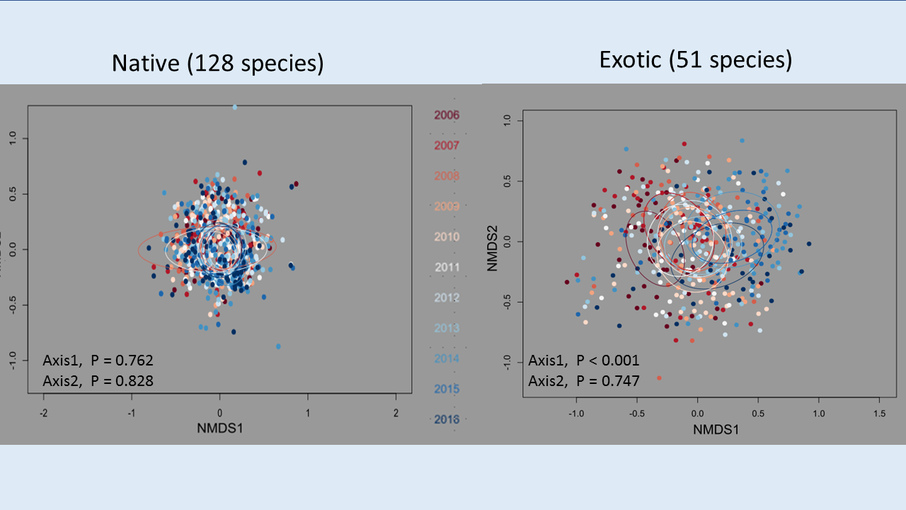

Detecting compositional change in plant communities

I am using multivariate analysis and machine learning tools to describe the changes in species composition in long term plant community data sets collected at McLaughlin Reserve (CA) and Tumamoc reserve (AZ). At McLaughlin, we have found consistent and directional change in one community, meaning that communities have become increasingly dissimilar in their composition over time relative to when surveys began. Additionally, this change is attributable almost entirely to exotic species. These results were surprising, since previous work has shown that reductions in species richness in the same data set result from the local extirpation of native forbs. Significant changes in composition were also linked to reductions in specific leaf area within plots, although the species most strongly associated with change do not consistently follow this community level trend. There is some evidence that phenological differences in reproduction may better explain changes in abundance in these populations.

I am using multivariate analysis and machine learning tools to describe the changes in species composition in long term plant community data sets collected at McLaughlin Reserve (CA) and Tumamoc reserve (AZ). At McLaughlin, we have found consistent and directional change in one community, meaning that communities have become increasingly dissimilar in their composition over time relative to when surveys began. Additionally, this change is attributable almost entirely to exotic species. These results were surprising, since previous work has shown that reductions in species richness in the same data set result from the local extirpation of native forbs. Significant changes in composition were also linked to reductions in specific leaf area within plots, although the species most strongly associated with change do not consistently follow this community level trend. There is some evidence that phenological differences in reproduction may better explain changes in abundance in these populations.